I Had to Flee Iran because of Cartoons I Drew at Eighteen

If I could rewind time, I'd do it all again.

Six years ago, I was a desperate 18 years old girl finishing high school in the small provincial city of Khoy, Iran. Depressed, and hopeless, I felt I could no longer hide my burning anger towards a patriarchal world in which men and the dictatorial political structures treated me not as a human being, but an object of possession. I had to do something.

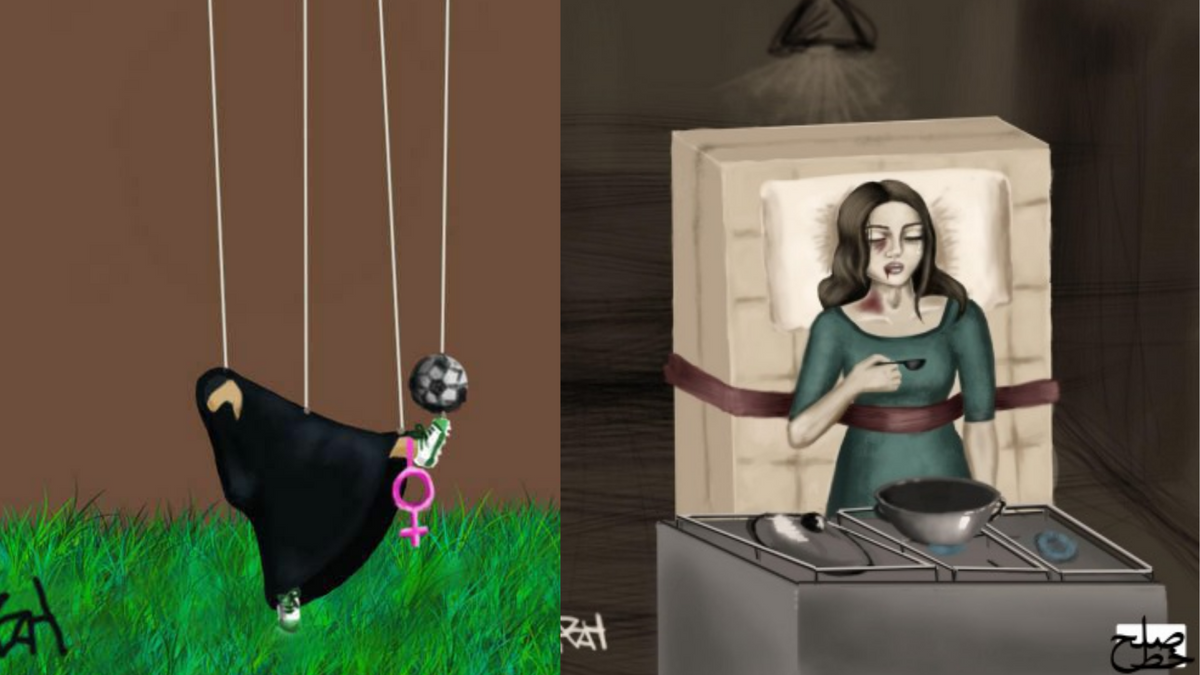

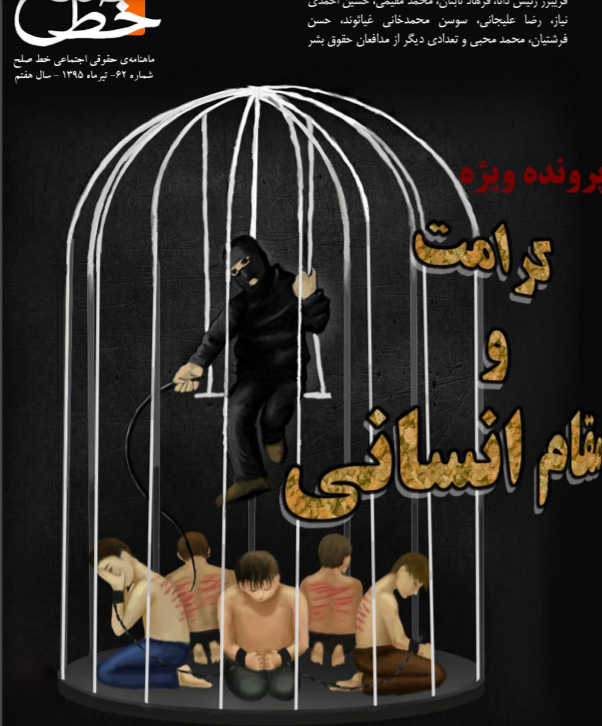

Having drawn some cartoons, I looked up the email address of the dissident HRANA magazine, and sent them there. I penned the email under a pseudonym: GhazalShabah (Ghost Poem)—I felt the regime had reduced women to the status of ghosts, invisible in public life—unable to write under our own name, forced to live behind the walls of home, under the tyranny of compulsory hijab and facing the injustice of pseudo-religious law.

The regime of Iran calls their lawless barbarism velayat-e faqih—Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist—but this is not based in reality. There is neither true religion or true law in dictator Khamenei’s Iran.

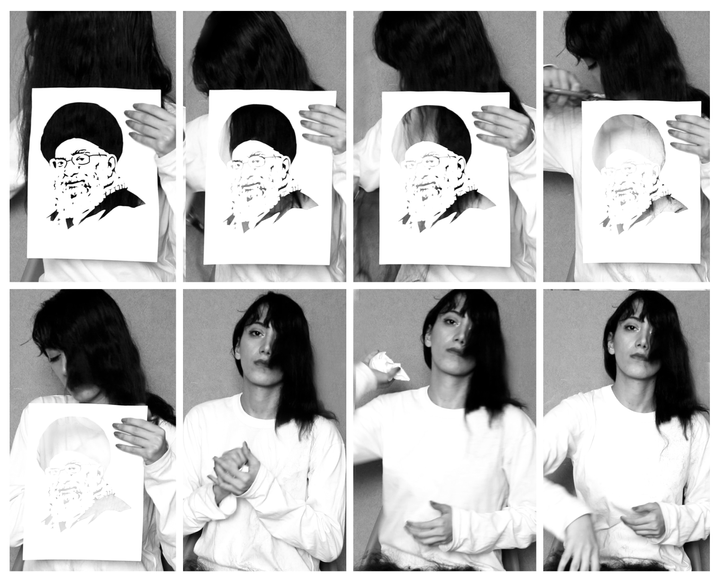

The Iranian regime does not worship god or even any version of Islam—they worship the idol of Ruhollah Khomeini: The self-proclaimed cleric who founded the so-called “Islamic” Republic of Iran after the revolution in 1979—an anti-Semitic, patriarchal and truly godless man without intelligence.

They hang his picture in public places (although, ironically, strict Islam prohibits such public idolatry). They worship him like Nazis worship the image of Hitler, or communists worshiped the cult of Stalin. The true system of Iran should be called velayat-e kir: The guardianship of the penis.

One particularly egregious expression of this is the legalized form of human trafficking called Sighe—temporary marriage—which can be as short as one hour—with exploited women, often migrants or women from ethnic minorities, who have no way to defend their rights, and who often don’t even have a state ID card. Temporary marriages are available for any man who wants them, regardless of whether they have a wife or children at home. Men can “order” these exploited women on “introduction” websites, where the prostituted women don’t have names, only a numerical code: Like the barcode on a potato in the supermarket.

Another part of Penis Guardianship is no criminalization of marital rape. Thus, powerful men can use their wives as sex slaves or exact even their sickest fantasies on them. This is the reality of a barbaric system that puts men—their penises, their superstitions, their whims—over any concept of law, morality or religion.

Many young people accept this system of lies to continue living their carefree lives of domestic comfort, but it breaks them from the inside. Depression, addiction, and alienation come hand in hand with the silence. Those who resist are broken by the regime from the outside. In my case, my teenage cartoons came to haunt me six years later. In no small part because of them, I was forced to leave my beloved homeland, my family and my friends. It compelled me to escape to a drab city 1000s of miles away from my birthplace.

Here, snow already covers the horizon in early October: a culture shock that was more difficult to bear for a child of the almost everlasting hot Iranian summers like me than many bureaucratic trepidations (now I was to walk around in a heavy winter coat that feels like I’m wearing my bed’s blanket on my shoulders). But still, I have never regretted my choice to draw the cartoons—and I hope my story can inspire every fellow young woman who reads this to resist the patriarchy too, no matter what the obstacles and punishments.

Six years ago, the anxious self-doubting teen in me never expected that my email to the dissident HRANA (Human Rights Activists News Agency) magazine would even get a reply: Not because of politics, but because I couldn’t imagine my art would be good enough for such a well known opposition magazine.

But, oh my, HRANA not only published my cartoons—the cartoons of a random, pseudonymous teen. They put one of my cartoons on the cover page of their magazine. I’ll never forget the feeling of belonging and purpose I experienced when I saw those cartoons in their published form. I had always thought my drawings would be meaningless.

After the pseudonymous cartoons were published, life carried on in a creepily mundane way. I went off to the university and my life was once again filled with more practical, everyday-type challenges. I sent no further cartoons. Every time I drew some I felt they weren’t as good as the published ones, and I threw them in the trash.

University was a cauldron of simmering, diffusely dissident ideologies. It was a predictable reflection of a polarised country in which almost everyone can find something to dislike about the ruling regime, but where no one can find any agreement with their fellow citizens on what to replace the regime with or how to do so.

My own experiences of forced assimilation and discrimation – I come from the South Azeri ethnic group – tempted me towards the easy allure of vengeant pan-turkic nationalism, and distracted me from my feminist self-education. I attended underground political meetings, and posted simplistic things on social media on my pseudonymous accounts, some of which I today regret. This was a passing phase, I never really joined any political cause, not in heart and not on paper.

Later, inspired by academic liberalism, I worked on social media projects to connect the different ethnic minorities of Iran: Baluchs, Arabs, Armenians, Lurs, Jews, Kurds, Turkmen, Azeris and many others to call for a society without structural racism and pan-Persian cultural assimilation. On Instagram and elsewhere, I connected with ethnic equality activists, including those living in political exile abroad. I organised meetings for fellow students from minority backgrounds, little study groups against pan-Persian assimilation. In this time of hot-headed ideological experimentation, I almost forgot about the feminist cartoons I had drawn back then.

That was until, in April this year, I received a call from an unlisted telephone number, summoning me to an interrogation appointment with the security services in my home city of Khoy. One of the gut-wrenching things about these calls is that the officers never tell you why exactly they chose to summon you: Maybe I talked to one-too-many exiled ethnic equality activists from abroad, maybe it was because of my social media posts, or maybe just because of an old-fashioned denunciation from a fellow student in one of the study groups I had organised. I’ll never know.

After a sleepless night of fear, I went to my interrogation appointment. Ghoulish officers asked me a repetitive catalogue of questions, intimidated me, and forced me to sign a bunch of papers where I formally pledged not to involve myself in politics again. Then they let me go, almost as suddenly as they had called me.

In a way it wasn’t surprising – if the regime were to immediately jail every young ethnic minority person who complains about racism and demands self-determination, even its copious jails would overflow. Iran is just too structurally racist for the regime to be able to expect any kind of appreciation from its non-Persian, minority ethnic citizens and it knows that. So a degree of grumbling and complaining is tolerated in the far-flung regions of the Mullah’s contemporary Persian empire, like the East Azerbaijan province.

After that, I went to the capital, Tehran, and spent over two weeks at friends’ apartments, trying to lie low, waiting to see what would happen. I told almost no one where I was, and started to persuade myself that everything may just have been due to the overzealous work of a local securocrat in Khoy.

Those soothing attempts at self-reassurance lasted until the day that officers from the main security services in Tehran knocked on the door of my hiding place, and asked me to accompany them for an interrogation.

”I was presented with heaps of printouts of my pseudonymous social media posts, which I had to sign and acknowledge as mine.”

This time, the questions were much less performative, checkbox-like. They were cold, relentless and probing, covering every aspect of my life, not just my activism for ethnic equality. I was presented with heaps of printouts of my pseudonymous social media posts, which I had to sign and acknowledge as mine.

This time, I was only released on a bizarre kind of bail: One plot of my family’s lands would serve as a guarantee of my future attendance and cooperation in this investigation. The investigators felt that a small, physically lightweight ethnic minority woman like me would never disobey her family elders, cause them financial loss, or bring public shame to them, by disrespecting this forceful verbal instruction. As a result, my name was not placed on an official judicial blacklist. These servants of patriarchal power simply believed I was too weak to try to run away. Thus, they were sure it would be a waste of time to fill out the paperwork that would make running away impossible, to ban me from travelling or force me to regularly register with the police.

Less than two-months later, I was on a plane out of Iran. Walking past the passport control line at Tehran airport wasn’t a moment of happiness for me. I have never had a desire to travel, see the world, and unlike many other Iranians, I had certainly never been hunting for ways to emigrate.

Home wasn’t ideal, it contained a lot of pain. But still it was home – and I could hardly even imagine what it would be like to live without the sunshine of Khoy, without the buzzing communities at Tabriz bazaar, or without the beloved family members that I spent all my life around. But as the plane got ready for takeoff, I consoled myself with the idea that in a year or two, when some grass had grown over this investigation, I could quietly return home.

”I knew that from now on, my future, good or bad, would not be decided by mullahs, secret police agents, and the many soulless, corrupt people they have recruited as their informants and denunciators.”

I stayed in Turkey, temporarily, based on short-term visa-free touristic travel, and meanwhile applied to universities for temporary language courses. Eventually I was admitted to a Russian language program in a post-Soviet country. Even as I applied for the student visa, I never pondered staying abroad for long: I just saw it as a way to fill the void in my life with a new language until I could go back.

It was only in early October, after I had arrived in my new, post-Soviet destination, that the most bitter news came. There would be no quick language year abroad, but a much more permanent exile, frostily far from home.

A friend of mine in Iran, a young social media activist, had just been arrested in a brutal way by dozens of cops. I was informed that in jail, under physical torture, he had been made to tell everything he knew about me. That included my feminist cartoons for HRANA, including my real identity behind the artist’s pseudonym. There was no more middle way now. In the regime’s mind, a bit of petty student activism is one thing – illustrating the front cover of Iran’s number one dissident magazine is quite another: A matter of many years in prison. Now, all I could do was find a safe haven, make an asylum claim. I have always been reluctant, fearful to do so - a leap into the unknown, the burning of the last bridge.

I’ve often felt small, powerless, fearful. But I learned that when I face these feelings, they often disappears. I remember the fear I felt, the shaking of my body, the trepidation, before going to a lawyer's office, to begin the process of asking for political asylum. I felt far from home, out of place, scared. But when I actually walked into the office, and spoke to the lawyer, I felt no more fear: I didn’t feel good, I didn’t feel bad, I just felt alive. I knew that from now on, my future, good or bad, would not be decided by mullahs, MOIS (Iranian Intelligence Service) secret police agents, and the many soulless, corrupt people they have recruited as their informants and denunciators. Neither would it be decided by my family or the social norms of home. From the moment I walked into that lawyer's office, my story is mine alone. My life, my choice, my destiny.

In a way, that’s scary. But it is also strangely empowering. If I could rewind time to that moment when I was 18 and about to click the send button on the email with those cartoons, I would do it all again, even if I would know that those cartoons would one-day cost me my home and turn me into a refugee.

4W provides paid writing work for over 50 women in countries spanning the globe. This work is made possible thanks to your support on Patreon.

Comments