Inside the Fight for Female Priesthood among Zimbabwe’s Baptists

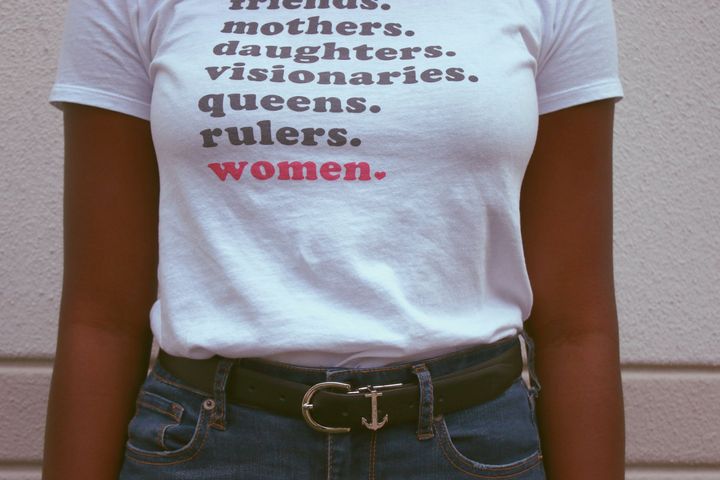

Women existing within the conservative dictatorship are quietly pushing back against a century of patriarchal tradition.

I ’m a 23-year-old black feminist studying food science at a university in Zimbabwe. My family belongs to a United Baptist Church, where I have dreamed since I was a child of being a priest.

This is 2021, and I would like to think our denomination, modelled on the values of the National Baptist Convention of America, is fairly liberal. But the path to priesthood in my Baptist denomination is blocked to me — women in our denomination are allowed to study theology and train as priests but are not allowed to serve congregations as priests.

Thus, in our denomination of 15000 members and 14 churches, we have hundreds of female theologians, some trained to masters and doctorate levels, barred from serving congregations as priests. The political, social, and economic climate in Zimbabwe severely limits women’s ability to speak out against this discrimination. But, nonetheless, a quiet discussion is happening behind the scenes, pushing the denomination, and the country with it, closer to progress.

Background: Zimbabwe’s Baptists

In the late 1800s settler missionaries from the Southern Baptist Convention in Augustina, Georgia landed in what is now called South Africa. They quickly began the task of pushing into the hinterlands to convert native African tribes to Baptist denominational values.

In 1913, the American Baptist missionaries established the first Baptist post here in Zimbabwe, and thus began a process to establish native African Baptist churches. In 1950, the missionaries formally named my church, The United Baptist Church of Zimbabwe.

The Baptist church brought with it social services that improved the lives of many generations in Zimbabwe, the impacts of which are still felt to this day. They built non-discriminating public hospitals which deliver births, feed orphans, and treat illnesses for free from Malaria to tuberculosis to HIV.

“The political, social, and economic climate in Zimbabwe severely limits women’s ability to speak out against this discrimination.”

The church was also responsible for improving Zimbabwe’s education system, erecting low-fee dormitory schools which are responsible for educating future leaders of our country.

I am, myself, a beneficiary of the Baptist legacy of educating both black women and males here in Zimbabwe. The Baptists have helped make Zimbabwe one of the countries with the highest literacy rates on the African continent. However, 100 years after landing on the shores of Algoa Bay, the Baptists remain staunchly opposed to women’s theological progress.

Sexism in the Church

There are dozens of superbly educated female believers, PhDs, Masters, bachelor degree holders who have graduated from our very own theology college. They are women of zeal, repute and unquestionable academic credentials and usually gradually on top of their class. Yet, they are still prevented from serving as priests.

As a young lady I have probed questions about this dilemma to my mother who is a devout Baptist like everyone in my family.

“Why are educated female theologians sitting at back benches in our church?” It was a troubling ask.

“St. Paul commanded in First Timothy 2: 11-15 that a woman must not lead as a priest. So says our church,” mused my mother, who herself is a history university graduate and a high school teacher.

This is the whip that the exclusively male board of our church uses to put educated female theologians “in their place.”

“Zimbabwe’s strict political dictatorship and patriarchal family dynamics keep women tightly bound to the church of their family.”

Every Sunday, women are humiliated to see less qualified male preachers lead sermons, incorrectly interpret scriptures, and conduct Holy Communion while female church theologians (some with PhD degrees) sit at the back of the benches, muted, twiddling thumbs.

But the Baptists are not the only denomination in Zimbabwe. The Methodists, located right next door to my Baptist church and also remnants of the American missionaries, are actively educating their women and ordaining them to serve as priests. The Methodists here in Zimbabwe chose a liberal path 40 years ago when Zimbabwe became independent from British colonial rule. In the post-colonial epoch of the 80s, black Zimbabwean Methodist women were clamoring for the civil right to serve as priests. The Methodists relented, while Baptists held tight to tradition.

But for Zimbabwe’s Baptist women, born and raised in the denomination, ascending the theological ranks is not as simple as switching denominations. A combination of factors including Zimbabwe’s strict political dictatorship and patriarchal family dynamics keep women tightly bound to the church of their family, prevented from branching out and forging their own path.

Trapped in the Church

Ever since I was a child, I wanted to be a priest. I dreamt of conducting weddings, burials, and baptisms for the members of my community. I wanted to serve my people, and do so as a woman. I know that my religion does not value me because of my sex, and choosing to serve a more progressive denomination may appear to be the obvious solution. But walking away from Baptism to a more liberal congregation is not as easy in Zimbabwe as it may sound to Westerners.

Religion in Zimbabwe is tied to the ropes of politics, economics, and family-level control of women.

As an impoverished country, most children remain under their family roof until they marry — this means that adults as old as 27, sometimes, often still live with their parents. Children, even into adulthood, are expected to submit to the father in order to receive the benefits of his care, including food, clothes, education, and housing.

“You leave our church, you start paying your own life bills,” young women like me are told by their families here in Zimbabwe.

“To rebel is to find oneself on the streets, your college tuition withheld, told to fend yourself immediately in a country with one of the world’s hungriest populations.”

This is not an empty threat, especially for female children. There are limited employment opportunities for women in Zimbabwe, a deeply conservative country where the UN Women says only 19% of women are employed above the international poverty line earnings.

For unmarried women, leaving the church of your family is the same as moving to the streets. Immense shame is also brought on her, further limiting her future prospects.

The situation is hardly better for married women. When a woman is wed, she is expected to leave her church and join her husband’s even if she doesn’t agree with that church’s doctrine. “Submission begins with abandoning your church for your husband’s,” pastors counsel women on the eve of wedding days.

The Baptists, like all churches here in Zimbabwe, are tied to entrenched political power. Zimbabwe is a strict dictatorship where freedoms taken for granted countries like the US, Australia, or UK, are heavily policed. Churches, be they Pentecostal, Baptists, or Indigenous walk a fine line. They must either deeply entrench themselves in the systems of political power, or fly under the radar to stay out of trouble. For example, the former bishop-head in my own church was once a deputy minister in a feared regime of the Zimbabwe government.

“To rebel against one’s church (or urge other young women to do so) here in Zimbabwe is to tickle the sensitivity of local political kingmakers.”

The political situation, coupled with tight family control, makes it risky rebellion to publicly flaunt my growing feminism and rebel by teaching other young ladies to leave the Baptists, a church that prevents them from becoming ministers. One, however disgruntled with church policies, has to tread carefully in case the secret police can visit you. To rebel against one’s church (or urge other young women to do so) here in Zimbabwe is to tickle the sensitivity of local political kingmakers. If a church elder reports you to a powerful political official, you may be marked as “difficult and dissident.”

This is why, though dismayed, I remain in my family Baptist church. To rebel is to find oneself on the streets, your college tuition withheld, told to fend yourself immediately in a country with one of the world’s hungriest populations.

To be clear, it’s not that I resent the Baptists; I respect the community healthcare and education work they have done over 100 years in Zimbabwe, but I detest their patriarchal stance on female priests (and other matters).

Fighting From the Inside

There is no one-size-fit all solution against ending patriarchal religious practices. What works in New York does not necessarily work here in Zimbabwe. Women in the US have inspired us (from a distance) in the last five years with the #MeToo movement and, in the process, scoring victories with several sexual violence perpetrators arrested. But the US is a relatively safe democracy and women can, to a certain extent, push against misogyny in church or society without meeting serious, violent, retribution.

I’m not so naïve to suggest that a public visible MeToo-like movement to challenge patriarchy in churches here would be received so well as in the US. Feminism in Zimbabwe’s churches, universities, or streets is conflated with political rebellion. The consequences are severe for women.

“Debate that is gradual, careful, and sustained should be encouraged in repressive societies like here in Zimbabwe.”

But change must come and, if I don’t attempt to change it, a generation of female Baptists will come after me, still limited by the present patriarchal rules.

To start, we must open the doors to debate. We must test the waters, exchange insights with other women, poking and prodding into feminist urges (as I am with my own mum). Debate that is gradual, careful, and sustained should be encouraged in repressive societies like here in Zimbabwe.

Hence, I’m working from behind the scenes, writing, decrying misogyny in my church, one essay a time, from behind the scenes.

About me: Audrey Simango is a feminist, freelance writer and food science student in Harare, Zimbabwe. My work appears in Remedy Health Media and Newsweek.

4W provides paid writing work for over 50 women in countries spanning the globe. This work is made possible thanks to our paid monthly subscribers. Join today to support our work!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments