Write Only If You Absolutely Must

Even for a best-selling radical feminist author, getting published is not easy.

Editor's Note: This is a copy of a speech delivered by Phyllis Chesler at the Women's Declaration International (WDI) USA national conference on 9/25/22, republished here with permission.

Were I to tell you how hard it is for most writers to survive, get published, keep getting published, you might not believe me. And I want you to write—but only if you’re a writer, if writing is the way you breathe. Otherwise, as the Ancient Mariner once said: "Turn back before it’s too late." But if you ARE a writer—then you must write because you cannot live without doing so.

Words matter. Language matters. They can enlighten, inspire, entertain, and support a feminist awakening. They did. They can also function as our legacy to the coming generations.

It is our enormous privilege to be literate and educated and for some of us to be able to publish books, articles, poems. Historically, most women were not taught to read and write and were frowned upon if they wanted to publish. Even the great George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans) published under a pseudonym.

But here’s a necessary perspective.

Many (white, male) writers throughout history have also suffered from both poverty and plagiarism. If they were not born rich, they all had day jobs. Many were never paid for their published writing. Some had to PAY to be published. Writers—even the greats—also suffered scathing reviews. Some were censored, their books burned. Some were imprisoned, sent into exile, or murdered for their thought crimes either against religion or against the state.

In our time, our work, especially our best and most radically feminist work, simply goes out of print and stays there. It dies softly. It does not get translated into other languages. We are lucky if it is noted at all, even if only to be critically savaged. More often, it is simply not reviewed. The tree falls, no one hears the sound.

“Our work, especially our best and most radically feminist work, simply goes out of print and stays there. It dies softly.”

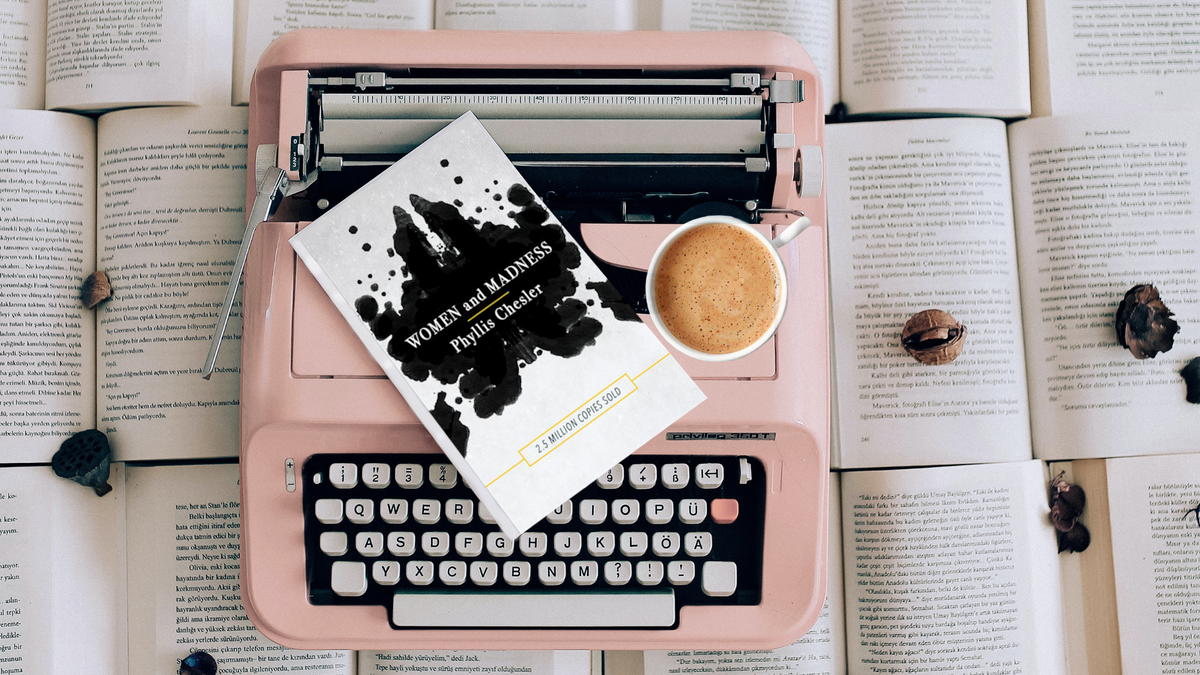

Even a radical feminist writer such as myself who was blessed to have published a bestseller—“Women and Madness”—never had such a best seller again. The large publishers hold this against you. Yes, I continued to write landmark feminist classics—(Mothers on Trial, Letters to a Young Feminist, Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, An American Bride in Kabul, A Politically Incorrect Feminist, Requiem for a Female Serial Killer)—but increasingly, publishers were only interested in my—in every writer’s sales records and they’d decline to publish you or give you increasingly tiny advances if you did not have bestsellers.

I had a great run—and I’m still here, still writing and yet….

When people ask me how long it took to write my first book, Women and Madness, I usually answer: my entire life. It also led to countless sorrows for me. My university colleagues feared, envied, and perhaps even hated me for my sudden prominence. They made my academic career a permanently uphill ordeal. Some feminists scorned the success; those who had demanded that I publish “anonymously” and donate the proceeds to the “revolution” stopped talking to me.

However, buoyed by a rising feminist movement—this was the late ’60s and early ‘70s—I coasted my way through the many patriarchal assaults and university-based punishments launched against me.

But, despite publishing quite a lot after that—I also perished, institutionally speaking. It took me 22 years to become a full professor, my tenure was challenged again and again, as were my promotions (which determined one’s salary and one’s pension). I never received a serious (i.e., tenured) job offer at any other university.

Nevertheless, that first book of mine was embraced by many millions of women. It was reviewed prominently, positively, and often. However, it was also damned. Psychologists and psychiatrists were offended, enraged. I was certainly not invited to lecture to such groups, at least not until feminists had more senior roles within them.

“Today, a feminist cannot be “politically incorrect,” not even in a book with that precise title.”

And I’m a “successful” feminist writer. Just think about those who are not visibly “successful,” whose work is excellent but has been forgotten, “borrowed,” not cited, laid to rest before it could do its considerably good work in the world.

Today, a feminist cannot be “politically incorrect,” not even in a book with that precise title. In this 2018 work, I was not allowed to write at length about my 21st-century preoccupations, which include the rise of antisemitism; the Stalinization of feminism, the ways in which anti-racism pre-empted anti-sexism, the renaming and demise of Women’s Studies—subsequently titled Gender Studies and sexuality, or LGB—but especially Trans Studies; the significance of Jihad terrorism and Islamism for feminism; the dangers of identity politics; the nature of honor-based violence, including honor killing—I’ve published four pioneering studies on this subject which have allowed me to submit affidavits to judges in political asylum cases—all these subjects were deemed too politically incorrect and not part of the earlier, more acceptable, and more “positive” moments of the liberal and left Second Wave.

I don’t think what happened to me was unique. I believe this was and still is happening to many other authors, too. It’s just that nearly 60 years in the writing life did not spare me.

If you’re white and not focusing on anti-black racism; if you’re a straight white male and not trans; if you’re a Westerner and not from Africa, Asia, or South America; and if you’re a radical feminist focusing on women’s sex based rights—your work may not get published or reviewed.

Here’s what happened to me in terms of one book. I had to do mortal combat with 4,000 editorial challenges and demands (yes, I counted them up) made by at least two, but probably by three different editors. No one editor had seen what the other two editors had to say. This felt like a prolonged assault. It did not improve the writing so much as provide the editors with an opportunity to knock the work down, not elevate it.

A chapter in which I critiqued identity politics was rejected outright. The publisher was afraid of legal, critical, and perhaps even violent repercussions. I questioned, no, I deplored identity politics. I questioned the use of gender over sex. I viewed this as dangerous. I went through every one of my own “identities” to reject each one.

My work was not done after wrestling the 4,000 challenges to the ground. The manuscript was then submitted to two outside “sensitivity” readers, one for race, the other for gender. Had they only been as literate as I was, it might have been acceptable, but both lacked my knowledge base. These were terrifying and demoralizing experiences.

One of the two or three editors—I’m not sure which one—demanded that I attribute the song Embraceable You to Nat King Cole or I’d be seen as an ignorant racist. But the song was written by two white Jewish boys (George and Ira Gershwin); Ginger Rogers first sang it in a musical in 1930, and the divine Billie Holiday made it her own in 1944, all long before Nat King Cole’s mellow rendition ever appeared. No matter.

“It does not matter if you’ve been a bestselling author or a legendary pioneer. Nothing will spare a writer from such nervous scrutiny.”

Bad things continued to happen. My editor was “let go” for corporate reasons. This orphaned my book. The editor who inherited the work barely read it. She was also too busy to meet or even talk to me. She had an option on my next book which she swiftly declined. My agent then refused to represent that work.

The editor who inherited me chose to rush it out with a lead time of about two or three months, and with a pub date of Aug. 28, a time of year when everyone is away. I could be wrong but I doubt they sent out copies to the right potential reviewers. They probably did send them to all the precisely wrong reviewers, and to only a few of them.

Unbelievably, the printer managed to drop 40 pages of a science fiction novel right into the middle of my book. I only found out about this when a few readers who knew me reached out to me. The publisher shrugged it off. “This happens.” Although they paid me to read for the audiobook, they chose not to publish a paperback version of this title.

And then the publicist told me, with great disappointment, that it was too late to book readings at Barnes & Noble—and that only one bookstore was even willing to have me at the end of August.

“What bookstore is that?”

“The Rare Book Room at the Strand.”

Oh, I was in heaven. I may have spent a quarter of my life browsing there. The venue had sentimental value to me and it represented a love of books that is missing from the chains.

At the last moment, I managed to fill the place with more than 100 people and I hope that a good time was had by all. It aired several times on C-SPAN. I also read at a wonderful store, Book Culture, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where a spirited Q-and-A took place.

That was it. No editor ever appeared to greet me, support me, see me in performance, take me out for a drink.

In these times, every author, not just me, faces such ordeals. It does not matter if you’ve been a bestselling author or a legendary pioneer. Nothing will spare a writer from such nervous scrutiny.

Look: Walt Whitman had to self-publish. Herman Melville was very negatively reviewed and had to work as a customs inspector. I could go on. You get my point.

I will close with a reading. I found some long forgotten notes that I’d prepared for a writing workshop I gave in Assisi, Italy.

A READING. ABOUT WRITING.

"I write, because I can't not write, it's in my blood, it's how I breathe, feel alive, powerful, joyful, connected."

Long after I wrote this, I found that Pablo Neruda, in a Paris Review interview had said:

"For me, writing is like breathing. I could not live without breathing and I could not live without writing."

I do not fear the empty page. I have never suffered from writer's block. I have been blessed: My subjects find me, claim me, I never have to look for them.

Thus, envy has been my lot.

It's as if the world of non-writers know that a writer loves to write, can't not write, so they'll be damned if they're going to pay someone to do what they love to do in a world in which people are paid, either too little or too much, to do what they hate to do.

“I had to write every day, all day, so that in case Inspiration wanted to come by, She'd know exactly where to find me.”

I have been writing all my life, but I never took a class in writing. I read books: incessantly, intensely, from the time I was three or four years old. I read to escape my childhood and family life; I read to save my life. I started writing when I was eight years old. I've never stopped. I had no role models.

I used to say that I had to write every day, all day, so that in case Inspiration wanted to come by, She'd know exactly where to find me.

Most writers have fantasies about the Editor of Our Dreams. She or he is imagined to be our truest, kindest soul-mate, our secret therapist, Fairy Godmother (or Godfather), personal cheerleader, midwife, agent, companion, primary witness to our creation, our creativity. Friend, colleague, etc. I have never, ever had this. Which does not mean that I wouldn't like to. It does mean that a writer can actually survive without one.

Why do we write? Would we write even if we never got published, like the Buddhist monks who create elaborate, beautiful sand-mandalas, only to see them washed away by the sea? I might...But most writers, me too, have too much ego to knowingly, gravely, philosophically, send our words away, down to a watery sea-death.

RILKE:

“If one feels that one could live without writing; then one must not attempt it at all."

JOANNA RUSS “HOW TO SUPPRESS WOMEN’S WRITING WITHOUT REALLY TRYING”:

"She didn't write it. But it's clear she did the deed... She wrote it, but she shouldn't have. It's political, sexual, masculine, feminist. She wrote it, but look what she wrote about. The bedroom, the kitchen, her family. Other women! She wrote it, but she wrote only one of it. "Jane Eyre. Poor Dear, that's all she ever.." She wrote it, but she isn't really an artist, and it really isn't art. It's a thriller, a romance, a children's book. It's sci fi! She wrote it, but she had help. Robert Browning. Branwell Brontë. Her own "masculine side." She wrote it, but she's an anomaly. Woolf. With Leonard's help... She wrote it BUT..."

Russ could not get a publisher for this wonderful work. I know. I tried to help have it placed. Finally an academic press took it. It ended up at the University of Texas Press (1983).

VIRGINIA WOOLF “Shakespeare’s Sister” in A Room of One’s Own:

“What would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith? ...She a gift like her brother's, for the tune of words. Like him, she had a taste for the theatre. She stood at, the stage door; she wanted to act, she said. Men laughed in her face. The manager - a fat loose-lipped man-guffawed. He bellowed something about poodles dancing and women acting - no woman, he said, could possibly be an actress. He hinted - you can imagine what. She could get no training in her craft. Could she, even seek her dinner in a tavern or roam the streets at midnight? Yet her genius was for fiction and she lusted to feed abundantly upon the lives of men and women and the study of their ways. At last Nick Greene the actor-manager took pity on her; she found herself with child by that gentleman and so - who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet's heart when Caught and tangled in a woman's body? - killed herself one winter's night and lies buried at some cross-roads where the omnibuses now stop outside the Elephant and Castle."

***Now my belief is that this poet who never wrote a word and was buried at the crossroads still lives. She lives in you and in me, and in many other women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed. But she lives; for great poets do not die; they are continuing presences; they need only the opportunity to walk among us in the flesh.

4W provides a platform for over 70 feminist writers in countries spanning the globe. This work is made possible thanks to our paid monthly subscribers. Join today to support our work!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments