Dear Women: It’s Okay to be Disliked

(Especially if you’re trying to change the world)

Girls are conditioned from a young age to prioritize being liked and accepted above nearly all else. Pleasantness and agreeableness are important traits of femininity. In some ways, this is adaptive behavior: those who are accepted and protected by being part of an “in-group” retain privileges, access, and protection from that group. For our early hominid ancestors, being liked could be a matter of life and death — without your tribe, you were vulnerable. But now, thanks to social media and globalization, the whole world is our tribe, and the number of people we are expected to please has risen exponentially. While most people accept that they can’t be liked by everyone, being liked by at least most people can still feel like a life and death situation sometimes.

But, ladies, I am here to tell you one thing: it is okay to be disliked.

In fact, it may be impossible to avoid if we want to accomplish anything worthwhile in our human lifespans.

As someone with anxiety, being well-liked has always been a big deal to me. A few years ago, a single cruel comment on social media would haunt me for days. I would avoid being honest with people about topics on which I was passionate and just say what I knew they wanted to hear. Overall, I think people who met me did like me. I was pleasant to be around, polite, and respectful — the kind of girl that parents love. But I was also miserable.

I did not feel like my friends really understood me. I dreaded interacting with other people and putting on the act of “human socialization.” I used social media to project an image of myself without having to really engage with people, but then the lack of meaningful engagement on those platforms made me feel even more alone. Some nights, I would drink an entire bottle of wine and cry myself to sleep. Often, I thought about suicide. I was too concerned about being liked to be happy, or to fight to change anything.

Now, years later, I am widely disliked — but I’m also the happiest and most liberated I’ve ever been.

Finally, it feels like I control my own emotions rather than my mental state being in the hands of others. Rather than concerning myself with pleasing everyone, or even most people, I’ve come to accept that most people will dislike me. The few, who don’t, are the ones worth investing my emotional energy in. Therapy, growing up, and reducing my substance use probably have a lot to do with my improved mental state in general, but there was one experience in particular that helped me come to terms with being disliked: becoming an animal rights activist.

How I Became Okay with Being Disliked

Animal rights activists are hated by nearly everyone. Non-vegans hate us because we are trying to take away their burgers and bacon, and vegans hate us because we “make them look bad.” Nonetheless, my anxious self decided enough was enough and I showed up to my first animal rights protest in January of 2016 at the age of 23. I could not have imagined the impact this decision would have on shaping my next few years.

At first, I was terrified to speak up at the protests. Standing inside of the butcher aisle of grocery store yelling, “It’s not food, it’s violence!” did not come naturally to me and my voice would shake as I muttered the chants.

This form of protest was disruptive, rude, and uncivilized — that was the point. It went against every ounce of my female socialization. While, at first, I was too scared to even chant and just silently held my sign in solidarity, eventually I got used to making a spectacle and dealing with the blowback. Customer and employee reactions became predictable. Whole Foods employees will just stand back and watch, rolling their eyes while they wait for the police to come. Traders Joe’s employees get more riled up and were more likely to get in your face or attempt to escort you out themselves. Soon, the predictable nature of being disliked made it easier to cope with and I became more comfortable.

Over the next few years, I grew as an activist, and by 2018, I was leading groups of 200 animal rights activists to protests inside slaughterhouses — bartering with employees to save lives, or simply taking them if we had to. When lives are on the line, suddenly being liked matters a lot less than being effective.

Now, after switching directions to focus on fighting for women’s rights, I’m somehow even more disliked than I was as an animal rights activist. My notifications and comment sections are an absolute dumpster-fire of misogyny, threats, and hate. I have lost more friends than I care to count over this fight, been disinvited from conferences, and was even fired for my writing.

A lot of other women have asked me how I manage to be so brave in the face of the countless attacks feminists are still facing (even among progressives). Today, while I was sitting at a red light, the answer passed before me: a truck full of baby chickens on the way to be killed. A truck just like the hundreds I’ve seen before. A truck just like the ones we stopped with our own bodies to bear witness. A truck like the one we rescued June-the-chicken from after it crashed on a Delaware highway.

Facing down this immeasurable violence face-to-face, not behind the protection of a keyboard, gave me the bravery to be disliked. Now, three years later after I stood silently at my first ever protest, I know that I have relatively little to fear. I can be globally disliked and, as long as the cause is worth it, I will be okay. In fact, it seems that as long as you are trying to create change, being disliked is simply part of the package. Winston Churchill famously said:

“You have enemies? Good. That means you’ve stood up for something, sometime in your life.”

Activists throughout history have been persecuted, jailed, and assassinated for their work. Many of our heroes today were largely disliked in their time, even if they also had a dedicated following. If those who dislike you are the people in power, people abusing others, or people causing mass destruction, I would consider being disliked a testament to your character.

If we are disliked, this is nothing in comparison to the cost others have paid before us to allow us to even get to this point.

Coping With Being Disliked

Despite being reminded of the necessity of being disliked, it can still be hard day-to-day to live with the negative comments, hatred, and sometimes even violence being directed at you when you are disliked. Being disliked can have real, material, consequences on your well-being — such as the ability to get or keep a job. Certainly, there are people who feel they can not even afford to be disliked since they have no safety net. A major part of becoming okay with being disliked for me was building my independence so that I could handle the material consequences of being disliked.

For women, this is even harder. Women on average lack the same access to resources that men have traditionally had, are more likely to be financially dependent on others for their survival, and are more likely to be the sole providers of children or their parents. The precarious position of many women in society means that being liked can feel like a matter of survival. Even if none of these things currently applies to you, perhaps it once did — or perhaps your mother instilled in you the importance of being liked because these things applied to her. This may be part of why for women being disliked feels so earth-shattering.

The emotional toll that comes from being disliked, even if we know our cause is worth it, can be heavy. While we accept that it may be okay to be disliked by huge swaths of the population, accepting the inevitability of this outcome for activists does not mean that we should not have support systems in place. Being open and honest about who you are and what you stand for means that the friends you gain along the way, or the ones who continue to stand by you, will be your true friends — ones who are there for the right reasons. Weaker friends have weeded themselves out — like one “friend” who helped me edit a piece I was writing and supported my work until I started to receive public blow-back for the piece. Then she suddenly had nothing to do with it.

Despite having fewer friends now on paper, the friends I do have now I am so much closer to. I trust them because they have stood by in the face of enormous social pressure to do otherwise.

Perhaps the worst kind of dislike, though, is the criticism which comes from within the movement. Whether it’s other vegans or feminists — there are always those who are supposed to be on your side telling you that you are doing it all wrong. For example, I was recently called a “nasty bitch” by another (so-called) feminist and a former friend who realized she could gain attention for herself by attacking a public figure. Yet, overwhelmingly, the critics are those who are doing nothing themselves. Theodore Roosevelt stated (excuse the sexist language):

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; . . . who at best knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who at worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.”

He was right. It is easy to shout from the peanut gallery about how you would have done things differently, yet the critics themselves so rarely actually bother to put in any of the work themselves.

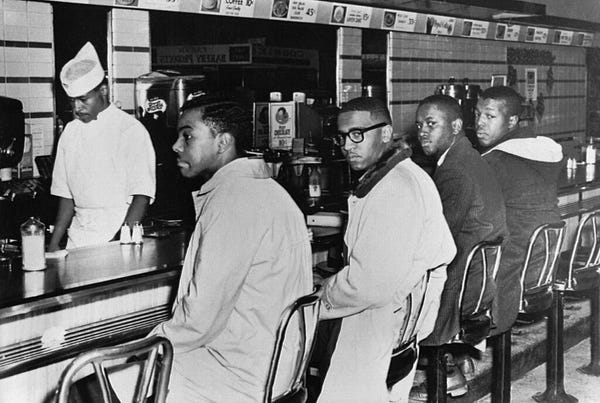

When the Greensboro Four held the very first sit-in at a segregated counter in North Carolina in 1960, there was a black waitress there who supposedly chided them for their actions, saying, “Fellows like you make our race look bad.”

Yet, the four students ignited a spark that set off a revolution. By the end of the week, over 1,000 anti-segregation demonstrators had filled the store. If Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Richmond, and Ezell Blair Jr. had listened to the naysayers on either side, the history books may have been written very differently on Civil Rights.

While we can always learn from feedback, for activists who are putting themselves on the line every day to actually create change, the nitpicking from our “allies” about how we are doing everything wrong is often best ignored. If their concerns are so genuine, perhaps your actions will inspire them to create something new themselves — which should be considered the greatest honor.

Be Brave — Be Disliked

While, certainly, there are reasons to dislike people that have nothing to do with bravery or standing up for what they believe, for most women, the fear of being disliked is what actively holds us back from doing these things and participating in the public arena to a substantial degree. For men, being disliked holds less social weight and is laced with fewer threats and consequences. For women, being willing to be disliked in order to fight for what you believe, is a political act in-and-of-itself.

As women, who are conditioned by society to prioritize being liked, the rejection of this feminine position is a defiant act of gender non-conformity. While you will certainly face consequences in your life for these actions, the impact of a single person’s bravery may be felt for generations to come — wouldn’t that be worth it?

The generous support of our readers allows 4W to pay our all-female staff and over 50 writers across the globe for original articles and reporting you can’t find anywhere else. Like our work? Become a monthly donor!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments