I Live 3 Miles from Where Sarah Everard Went Missing — London's Women are Terrified

"Is a uniform all that separates police from perpetrators?"

On 3rd March, 33-year-old Sarah Everard went missing whilst she was walking home from a friend’s house in South London. Two weeks later, police confirmed that her body had been found – and that one of their own, a Metropolitan police officer, had been charged with her murder. Her story has united London’s women in grief, shock and fear.

On the night Sarah Everard’s body was found, I received a phone call from an old colleague of mine. Under normal circumstances, we would have met up at a time like this – the idea of being in the same space as other women who were trying to process such heart-breaking news had never felt so necessary.

But lockdown restrictions meant we had no option but to support one another from a distance; to grieve together, but apart.

“I can’t believe it. She was in my friend’s book club,” she began, her voice faltering as she spoke. “It could have been any of us,” she added. Those words seemed to linger long after the call had ended.

Living just a few miles away, Sarah would have walked these streets. She would have visited the same local shops. Her eyes would have cast over the familiar skyline, where inner-city skyscrapers rise in deep hues of blue against the grey sky.

Nothing about her activities on the night she went missing were out of the ordinary. She was simply walking home from her friend’s house at 9pm.

I thought of the countless times I had walked home alone much later in the evening, wearing far less. I had flashbacks to Freshers week, some ten years earlier, where I had left a nightclub at around 1am. Dutch courage had left me feeling invincible.

"I can’t believe it. She was in my friend’s book club. It could have been any of us."

I was wearing a cheap red dress which rode up by my thighs. Somehow, despite being in a hazy state, I had followed my instinct and walked in the middle of the road, skirting along the dashed white lines. It felt safer to risk getting hit by a car than to be approached by a man at the side of the road.

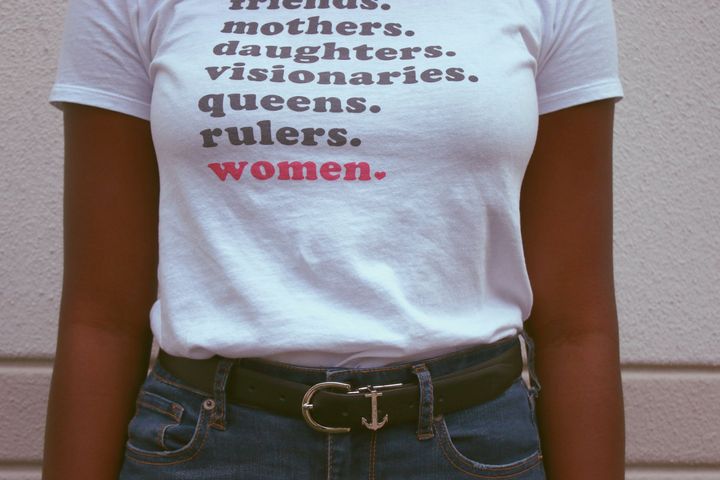

Passers-by (or anyone brainwashed by the patriarchy) could have accused me of “asking for it.” But Sarah could not so be accused – she had followed all the unspoken rules. She was covered up from head to toe, walking on a well-lit road, and on the phone to her boyfriend at the time she went missing.

Her story challenges the victim-blaming narrative churned out by the patriarchy, which places the onus on women to keep themselves safe from male violence.

But if a serving police officer is capable of femicide, how can women possibly protect themselves? Let alone distinguish who is trustworthy?

London’s women are understandably shaken. One such woman is 24-year-old Rachel Davis, a London-based reporter, who spoke to me about how the incident had impacted her. “It’s nothing new that I’m doing,” she said, “I’m just more hyper aware. Usually I am quite wary, and I wear comfortable shoes, bright clothing, and I try to carry my keys between my fist. I make sure people know where I am when I’m coming home.”

"There’s not really much the police can do if you've got no evidence."

“But it is easy to become complacent,” she told 4W, “sometimes I will just think ‘never mind, I’ll be okay…I’ll just take this shortcut’. But this has made me feel that I can’t, because the time you get complacent might be the moment something happens to you.”

Discussing the factors which enable misogyny to flourish, she added:

“I think it comes down to the fact that we live in a patriarchy and that men are allowed to get away with things. There's a rape culture of objectifying women, of not treating them as if they were full human beings. It’s okay to shout things on the street or to grab women or to touch them in a club or in a pub, or literally anywhere. And it's kind of accepted. There’s not really much the police can do if you've got no evidence. I hope that now misogyny has finally been made a hate crime in England and Wales (which for some reason, it wasn't before), that will help.”

Katy S., a 27-year-old woman who works in STEM, spoke about how the incident was not isolated, but fits into a culture of sexism, as outlined in a UN report finding that 97% of women in the UK have experienced sexual harassment:

“When I first heard the statistic, I thought I wouldn't consider myself in the 97%,” she said. “But then, when I started to think about it, there were dozens of incidents that have taken place that I just hadn't ever spoken up about.”

She says her experience is not isolated. “Literally every other young woman I've spoken to has experienced similar things. And I can't help thinking that those people in the three percent probably have experienced some form of misogynistic hate crime as well. But they maybe haven't realized or identified it, because it's just so implicit.”

Reflecting on her views toward police following the incident, she added:

“It does decrease my trust in police. Yesterday, there was a police officer who had been convicted of being a Neo Nazi terrorist. You just don’t know who they are allowing in the force. But that said, I maybe haven't had too much confidence in them protecting women against these crimes anyway. I've been physically harassed a number of times, but I wouldn't ever feel like reporting it because I don't think they have the resources to investigate it.”

Another woman, a 28-year-old child protection social worker who wishes to remain anonymous, shared how close to home the incident felt. “It really just made me feel pretty more worried, more scared,” she told 4W.

She added that she thinks Sarah’s case is getting more attention in the media because of how she fit the “perfect victim” profile:

“One of the children I work with asked why this case is so prevalent in the media. And I do wonder, I do have to question if she was a Black woman like me, or if she wasn't middle class, or maybe a sex worker, would it be in the news? And my answer is I don't think so – and that’s really sad. There was not nearly enough coverage for Blessings Olusegun, who was found murdered on a beach last year in similar circumstances, and the police still don’t know what happened to her. I think there is institutionalised racism in the police.

In the wake of Sarah Everard’s murder, a generation of women are being awakened to the fact that the police, a predominantly male institution, are guilty of brutality against oppressed groups – something the black and minority communities have been trying to communicate for years.

And the police are still trying to uphold structural oppression by yielding to those in power, as has been evident in their victim-blaming approach to Everard’s death.

Days after her disappearance, police instructed women not to go out alone, implying that they were putting themselves at risk by simply existing in public without a chaperone (as if we are still in the 1800s) – rather than addressing the root case, male violence against women.

"If she was a Black woman like me, or if she wasn't middle class, or maybe a sex worker, would it be in the news?"

The advice was shockingly ignorant. It was almost as if it had never dawned on police that women, fearing for their safety, are already under an unwritten law to say inside after hours (lockdown or not).

When Baroness Jones, a leader of the Green Party sardonically suggested that men have a curfew instead, there was moral outrage. The backlash highlighted the level of entitlement felt by some men, who were clearly so accustomed to the privilege of dominating spaces that it had never occurred to them to even acknowledge it – let alone change it.

The police took a similar approach at the very vigil which took place for Sarah, the woman killed by one of their own, when male officers were filmed manhandling grieving women. Rather than respect women’s already-threatened spaces by implementing boundaries, these officers violated them.

Later, the head of the force attempted to gaslight women by claiming the police “acted appropriately,” despite photographic evidence to the contrary – effectively using the same tactics employed by domestic abusers.

Perhaps what the police forget is that their so-called “appropriate actions” would never have been necessary in the first place, were it not for the fact that one of their own kidnapped and murdered an innocent young woman.

It is increasingly obvious that the police are institutionally misogynistic. However, this cannot be divorced from institutionalised racism; the two are inextricably linked.

In the fight to protect all women, it is crucial to adopt an intersectional feminism, described by American law professor Kimerblé Crenshaw as “a prism for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each-other.”

In doing so, we can begin to recognize the double jeopardy of sexism and racism experienced by Black and minority women, which threatens them both in life and death.

When black sisters Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry were found dead in a park in London last year, white male police officers took selfies with their bodies, demonstrating a lack of respect for which there are simply no words.

In an interview with the BBC their mother said, "If ever we needed an example of how toxic it [the Metropolitan police] has become, those police officers felt so safe, so untouchable, that they felt they could take photographs of dead black girls and send them on.”

"Is a uniform all that separates police from perpetrators?"

But the families of Nicole and Bibaa still lack justice. To this day, no officer has been charged over the offence.

It begs the question - is a uniform all that separates police from perpetrators? Sarah’s story, among countless others, suggests that they are merely two sides of the same coin.

A badge and a pair of boots does little to rid men of the desire to enact male violence and terrorism against women; if anything, the unchecked power and status often provides a literal “get out of free jail card” for abusive officers.

Far from what we were taught as children, there is a duality to the role of the police; they are capable of being both “rescuer” and “perpetrator” — and the former role is often used as a gateway through which to gain access to, and exploit, women.

But the narrative is changing. Women everywhere are waking up to the fact that we live in a vicious cycle, where we essentially pay misogynists to protect us from themselves. We are coming to grips with the reality that the police are just another facet of male violence. That there is something intrinsically flawed about a system where we have no option but to call upon another branch of oppressors when in danger.

Only when we know about the violence women and girls face are we able to make a difference. Help us expose male violence by becoming a monthly donor! The generous support of our readers helps to pay our all-female staff and writers.

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments