What If My Rapist Becomes Famous?

The new world order women live in.

We see the same question asked every time there are new allegations of abuse against a famous man: “Why didn’t she report it sooner?”

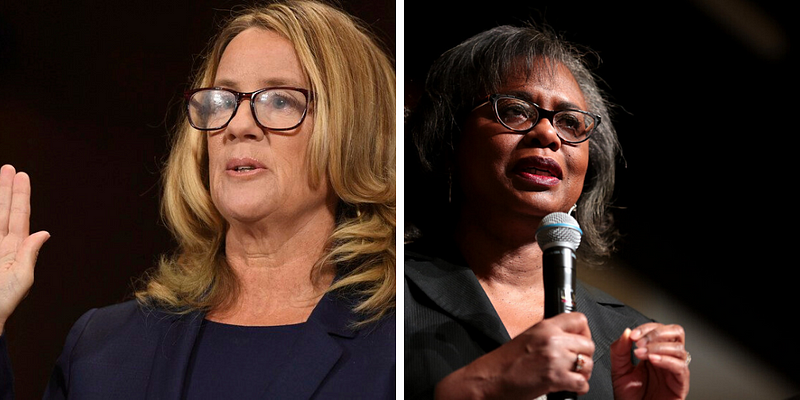

During the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh, critics of his accusers were quick to ask why women waited until his SCOTUS nomination to come forward with their allegations. (This is despite the fact that Christine Blasey Ford, for example, has many previous corroborating witnesses).

Of course, we pretty much know by now why women don’t report sexual assaults. Julie Bindel wrote in 2007 that rape was so hard to convict that it might as well be legal. It doesn’t seem much has changed since then. The fear of further traumatization, not being believed, the stigma associated with sexual assault, and fear of retaliation are enough to make reporting seem not worth it.

That is, until your rapist becomes famous.

After a series of high-profile accusations, women today are forced to ask themselves a new question when they weigh their willingness to report sexual assault or abuse: “What if I don’t report now, and he becomes famous later?”

Not reporting sexual assault in a timely manner often means that later allegations will be ignored, belittled, and held to extreme standards (which, to be fair, they are anyways). In 2019, women know that if they don’t report abuse today, that man could go on to sit on the Supreme Court tomorrow.

Despite the fact that brave women like Blasey Ford and Anita Hill have come forward about the abuse they experienced, two out of the six male justices on the highest court are known (by women) to be violent misogynists. A whole new generation of women and girls are being forced to mentally debate reporting in a completely new way as we watch the current events unfold around us.

The desire to make sure abusers and rapists don’t become famous isn’t just about petty revenge.

Women who have experienced violence at the hands of these men know that fame means power. In cases, the power they wield is structural — like the power that Brett Kavanaugh now holds over women’s lives. Men like this should not have access to that kind of power, and their victims know it better than everyone.

For others, like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, fame and power means access to young vulnerable women. The desire to make sure abusive men never become famous is about protecting future women and girls from the trauma and pain that we’ve experienced as well as preventing their violent and misogynistic attitudes from shaping the wider culture.

For most of us, our rapists and abusers will probably never become famous.

Yet, we are forced to wonder where to draw the line. If I saw my abuser was running for City Council, would I report him then? What if he got a small acting role in an off-broadway play? What if he became a high school teacher? Fame and power can come slowly and, in the internet age, women may be forced to watch their abuser rise into power, debating every step of the way whether or not it is worth it to come forward yet.

I’ve probably had this conversation with most of my female friends — nearly all of whom are survivors of male violence. Many women who share the fear of their rapist becoming famous have come up with ways to preserve their memory or records for the future, just in case. Some women are keeping folders on their computer, backed up in the cloud and hard copies, of screenshotted conversations. Others are carrying their journals from ten years ago with them into the future, refusing to let go of this piece of evidence, no matter how painful.

Many women express a wish that there was a better system besides precariously babysitting evidence for decades on end. The mental weight of constantly managing your future accusations, carrying around literal baggage of your trauma, is immense and can prevent victims from feeling like they can ever truly move on.

Sometimes, evidence can be lost or destroyed after years of carrying it, leaving women feeling hopeless.

Sometimes, women feel they have healed enough to get rid of the evidence themselves — only to regret it in a few months when the next high-profile abuse case hits the news.

“The mental weight of constantly managing your future accusations, carrying around literal baggage of your trauma, is immense.”

My friends and I have brainstormed solutions to this problem. One idea we developed was a bank of accusations that could be managed by a law firm. If you need to access that accusation in the future, the firm would be able to release the information, connect women who have accused the same person, and represent them. Ideally, rather than trusting a single law firm, the project could be managed by a collective of firms with various specialties.

Since I’m not a lawyer myself, I have no idea how feasible such a project could be. As a technologist, though, I’ve imagined ways that technology could solve this problem. A website could allow victims to securely submit a statement, upload corroborating evidence, and store the information for your future retrieval — all you need to manage is a password.

The website could do more than just provide cloud storage, though. For example, an automated system could let you know if other people have submitted accusations about the same person. An optional setting could make your statement available to be anonymously read by other victims of this person. Victims could then, based on reading the statements, choose to disclose their identity to fellow victims — connecting women who may otherwise have believed they were alone.

The service could even automatically submit a police report under certain circumstances — like if the statute of limitations on the crime was about to expire, or if Google News results returned a specific number of hits indicating a rise to fame of the accused.

Of course, the opportunities for abuse and violations of privacy in such a system are plentiful, and any such system would have to account for all of these risks.

It is deeply shameful that women even need to consider creating their own system to handle rape accusations. In an ideal world, sexual assault or abuse would never happen. In a less ideal but more realistic world, when it did happen, victims would have no issues reporting it, and rapists would be convicted at a reasonable rate.

Yet, it’s clear that we’ve made practically no strides to move society in this direction. Despite being a loud, outspoken, radical feminist, I still have not reported my own rape and abuse. The chances of anything productive coming out of it seem way lower than the chances of having extra stress, trauma, and victimization at the hands of “due process.” I have no intention to report it.

Unless he becomes famous.

Originally published in Fearless She Wrote, CC-BY-SA, M. K. Fain

The generous support of our readers allows 4W to pay our all-female staff and over 50 writers across the globe for original articles and reporting you can’t find anywhere else. Like our work? Become a monthly donor!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments