When Feminists Are Accused of Being Conservative

Denying women's speech by assigning it to men is just more of the same old patriarchy

If one is to believe mainstream discourse, a new class of Conservative Women has emerged. These “conservatives” aren’t like the ones of the past. They have spent years, sometimes decades, fighting for abortion access and reproductive sovereignty. They have campaigned against poverty and for increases to social welfare. They are proud to label themselves feminist and have a history of voting for progressive candidates.

So what makes them “conservative”?

They have spoken out against trans ideology or the sex trade as harmful to women.

My own experience, as a longtime progressive in a largely conservative nation, has taught me that this trend may have nothing do with women’s actual politics but may be rooted in a patriarchal interpretation of women’s speech.

In the fall of 2019, four years after I started a liberal feminist magazine in my small, Catholic-church controlled country, I “came out” as trans-critical to my social media followers. The amount of abuse I received as well as its contents are now so ubiquitous, they don’t even need describing.

Desperate for support that wasn’t coming, I welcomed when an unknown man (I’ll call him Carl) contacted me with what I then interpreted as an expression of sympathy. At least, contrary to others, he wasn’t openly hostile. Carl as such is not interesting; but by being a typical male, he has, inadvertently, helped me shine a light on the topic of women’s speech.

Significantly, in his very first message to me, Carl said nothing about my situation or the abuse I’ve received. What he cared most about were other men. In particular, in his opening message, he called out the so-called liberal “pro-feminist” males who had, until that point, been my allies. Carl asked me, paraphrasing: “where are the men who profess to fight for women’s rights now that you’re receiving misogynistic abuse from the liberal side?”

"If a woman refuses to be a vessel for male words (whether on the left, right, or in the center), it’s as if she’s saying nothing at all."

A few messages later, my new acquaintance prophesied, half joking, that soon I might turn so conservative that from a blue-haired libfem I’ll suddenly become a housewife. In particular, he said that soon he might find me in the kitchen, surrounded by a bunch of kids, spending my days canning jams.

Being a woman who deliberately avoids all men (female separatist), criticizing both the left and the right of patriarchy, his prophecy seemed so out there that I didn’t even try to deny it. I had a sneaking suspicion he wouldn’t listen, anyway. While I didn’t have the words to explain the reason for these thoughts at the time, I do now: if a woman refuses to be a vessel for male words (whether on the left, right, or in the center), it’s as if she’s saying nothing at all.

If it speaks, it’s not a woman

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

The authors of the Bible make it clear: it wasn’t woman’s word that created the world. God is, after all, male. Nearly two thousand years after the Gospel of John was written, women’s words still aren’t heard.

“Women are systematically seen as less authoritative,” professor Jessica R. Preece says of her research into the topic of women's speech. She continues: “And their influence is systematically lower. And they’re speaking less. And when they’re speaking up, they’re not being listened to as much, and they are being interrupted more.”

In experiments with groups of five, researchers Karpowitz and Mendelberg found that women spoke less when they were outnumbered by men:

“It took not just a female majority but a supermajority (meaning four out of five) for women to finally speak their proportionate talking time. At best, outnumbered women in the study spoke three-quarters of the time a man spoke; on average, women spoke just two-thirds as much as a man."

Another example of women not being heard comes in the form of accounts by those of us who pretend they’re men at work (“trans men”). “Now that I pass as a man, people at work listen to me,” said a woman who identifies as a man in a 2020 report by the European Commission. Although different issues, such as the pay gap or sexual harassment make the headlines, when asked, the problem of being heard is what most of the “gender refugees” (“trans men”) choose to highlight after their pretence of being male is successful.

“Now that I pass as a man, people at work listen to me.”

I experienced this issue first-hand when working in an IT firm where most of my colleagues were male. Although I’d already noticed that my male friends often “switched off” when I started speaking, not being heard at work was unnerving on a very different level. In an environment where my success depended on communicating with others, their denial of my speech made my job impossible. Although I had entered the job as a woman confident in my own skills, in a matter of a few weeks I was left feeling worthless.

The refusal to hear me finally reached truly comical proportions in the very last conversation I ever had with my male boss.

Me: You know what? I’ve had enough. I quit.

Him (after a while): I think it would be best if we ended our cooperation.

In bed with other women

In the “trans wars,” women’s existence is being explicitly denied. Naturally, who doesn’t exist, can’t speak either. The denial of our speech often shows up in accusations of being "in bed with the conservatives.” There is no way, in the accusers’ minds, we could be “in bed with other women,” i.e. fighting (only) for women’s interests.

Unconsciously, “trans activists” express the supremely patriarchal view that “if it speaks, it’s not a woman.” The only way real speech could come out of women would be if the words were actually men’s.

“The denial of our speech often shows up in accusations of being 'in bed with the conservatives.' There is no way, in the accusers’ minds, we could be in bed with other women.”

Such a view of women is written into one of the founding myths of Christianity: Mary, mother of Jesus, became impregnated with the Word of God. By giving birth to this long-haired male utterance (Mary Daly called Jesus “transsexed Goddess”), Mary served as a vessel for making male words reality.

Throughout patriarchal history, the view of women as vessels for male creativity has been ubiquitous. In terms of women’s writing, Ellen Moers provided an eloquent example in her 1985 book “Literary Women.” About Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, she wrote:

“Her extreme youth, as well as her sex, have contributed to the generally held opinion that she was not so much an author in her own right as a transparent medium through which passed the ideas of those around her.”

Such “vesselism” hasn’t ended in the patriarchal 19th century. The 20th century still likes to deny women's creativity. Lundy Bancroft’s 1997 book “Why Does He Do That: Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men” makes a good example. Here, Bancroft quotes an abusive man (Sheldon) speaking thus about his partner: “I don’t consider her Ashley’s mother. She’s just a vessel, just a channel that Ashley came through to get into this world.”

Bancroft doesn’t tell us whether Sheldon is a devout Catholic. But that doesn’t matter. The truth is most of us in the post-Christian world have absorbed the messages of women’s vessel-like relationship to creativity. After all, Mary’s role in Jesus’s creation has been a major doctrinal point as well as a source of arguments between men for almost 2000 years.

To illustrate some of the differing opinions on Mary's creativity, we can look at Martin Luther and his disciples who rejected the Catholic church’s belief in Mary’s virginal birth. Quite hilariously, in the 2nd century AD, Italian heretics (Valentinians) believed that “Jesus passed through Mary like water passes through a pipe.”

(Pro)creation

In the post-Christian world, one area where the idea of women as mere vessels of creation manifests itself very obviously, is pregnancy and giving birth, including surrogacy.

According to a study by the World Health Organization, 42 percent of women surveyed faced obstetric violence, defined as abuse by health staff during or right after giving birth. However, speaking only about violence obscures the reason why it’s happening: the appropriation of women’s creativity and agency by men (or by token women, with the help of some females).

In Slovakia, where I am from, this theft of women's creativity clearly shows up in a saying hated by activists against obstetric violence. “Who birthed you?” new mothers in obstetric wards ask one another. They are not inquiring about their actual mothers. In this very frequently used expression, it is the doctor who “births” a pregnant woman. In this context, the verb "to birth" becomes something that is done to a woman. The subject of “birthing” is the obstetrician, who becomes a white-robed male mother.

Thus, in the hospital, a woman becomes an actual vessel: an object the health staff uses to bring a child into the world. Such a view of women, of course, brings forth violence. One extremely harmful practice, widely banned, but still routinely used in Slovak hospitals, is Kristeller’s expression.

Within this inhuman, painful, and dangerous practice, the woman is treated as a toothpaste tube: while she’s laying down on the bed, the staff push at her belly to speed the birth up – by literally pushing the child out of the woman.

“If a woman asserts her agency, whether in childbirth, in speaking, writing, or creating other original works, she will be ignored, ridiculed, denied, attacked, burned at the stake. ”

Treating a woman as a toothpaste tube is not far from viewing her as a water pipe, as gnostic Valentinians did in the second century AD. A vessel is a vessel is a vessel. But what if we refuse?

If a woman asserts her agency, whether in childbirth, in speaking, writing, or creating other original works, she will be ignored, ridiculed, denied, attacked, burned at the stake. Such was the fate of the women accused of Witchcraft during the European 15th to 17th centuries. The females who had no male protection, who were not useful to men, were the most frequent targets of inquisition.

As Mary Daly wrote: “the witchcraze focused predominantly on women who had rejected marriage (Spinsters) and women who had survived it (widows).” Daly drives this point further home by quoting Erik Midlefort. This historian called unmarried women of the Middle Ages a “socially indigestible group,” a fact that caused the Church wanting to get rid of them.

Futility of denial

The rejection of the notion that women could have thoughts, ideas, and politics independent from male control is baked into the very DNA of patriarchy. Women’s inconvenient politics, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum, have always been written off as an extension of the men controlling them behind the scenes (see also: “The boys are with Bernie”).

For those of us stumped over seemingly endless and unavoidable accusations of “being in bed with the conservatives” for speaking out against gender ideology or the sex trade, the urge to resist often comes in the form of listing our liberal/leftist bona fides. “But I am a feminist!” “But I have always voted for progressives!” “But I support leftist causes!”

“Women’s inconvenient politics, no matter where they fall on the political spectrum, have always been written off as being merely an extension of the men controlling them behind the scenes.”

No matter how much you try, no matter your progressive history or past activism, and no matter the accusers’ education, you will not refute the charges.

Once you realize this, you are free to examine the real problem at hand: you are a woman who is speaking words that have not been given to you by men.

Not only can this knowledge save you precious energy, it may also help you identify people able to actually hear women’s words. That way come true allies.

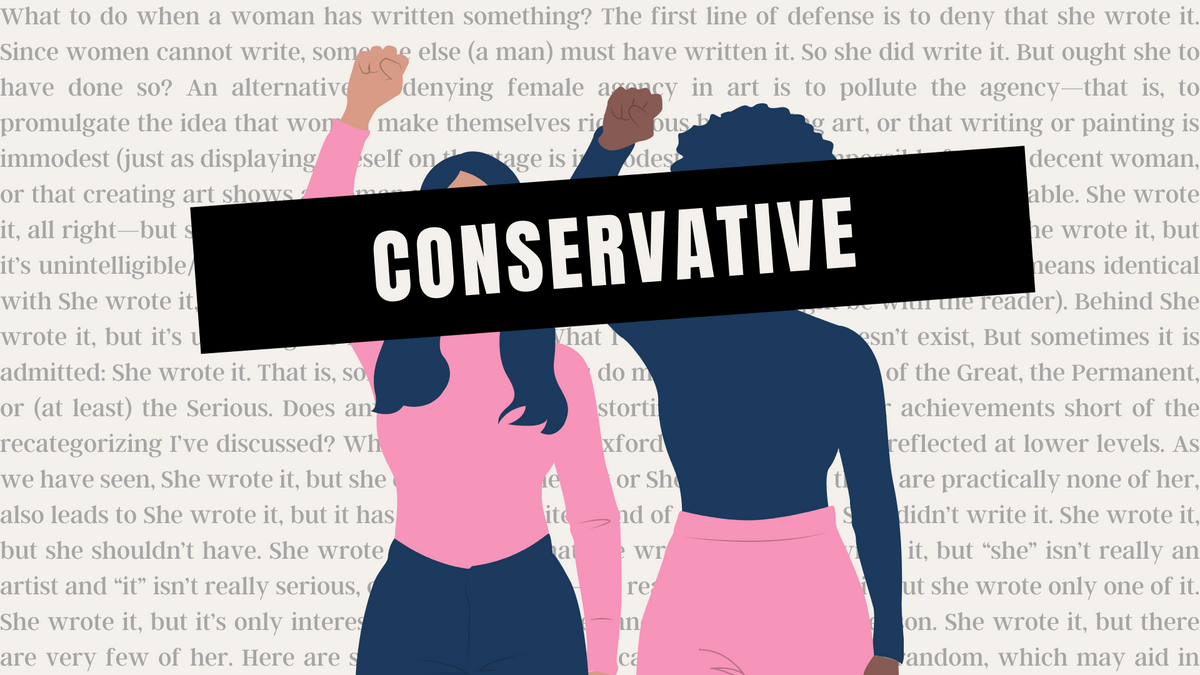

Text in the cover image includes selected quotes from Joanna Russ's 1983 book, "How to Suppress Women’s Writing".

Do you want to bring the "gender madness" to an end? Help us write about it! 4W is able to pay our all-female staff and writers thanks to the generous support of our paid monthly subscribers.

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments