Prostituted Women Experimented on For Decades in USA-funded HIV Trials Overseas

Trials of HIV prevention medications used thousands of vulnerable women in Africa and Asia, leaving some infected and sometimes in collaboration with pro-prostitution organizations.

Since the 1980s, women in prostitution in Africa and Southeast Asia have been used to test new solutions against HIV. Despite evidence of harm, the nonoxynol-9 spermicide was used on women and girls in prostitution leaving some of them infected with HIV. Although a similar series of trials were halted in 2004, this did not stop scientists.

Thanks to major US-based grants, new trials started collaborating with pro-prostitution organisations to gain access to women in prostitution. These trials were conducted on thousands of vulnerable women without true informed consent, leaving some infected with HIV.

Clinical trials target thousands of victims of prostitution in the 1990s

From the late 1980s, clinical trials on HIV were conducted on women in prostitution living in the poorest countries in the world. The nonoxynol-9 clinical trials aimed to ascertain whether nonoxynol-9, the most common component of spermicides used as contraceptives, could also protect from HIV.

In July 1990, a study on 138 mostly illiterate women in prostitution in Kenya was stopped early because a high number of women became infected with HIV through the study. A nonoxynol-9 vaginal sponge was believed to increase genital ulceration which in turn made women vulnerable to the virus. The study was funded in part by the American Foundation for AIDS Research, the National Institutes of Health, a medical research agency and Family Health International (FHI), an NGO based in North Carolina.

Sharon S. Weir, Ronald E. Roddy and Léopold Zekeng published their findings in 1995 on the increased risk of genital ulcers and HIV among 273 women in prostitution in Cameroon who used nonoxynol-9 suppositories. The study was again funded by FHI and USAID. Just a few years before, Ronald E. Roddy was involved in a study on Thai women in prostitution which had already detected the potential role of nonoxynol-9 in the increase of genital irritations and ulcers.

The same authors co-published a paper in 1998 confirming the findings. Over 1200 women in prostitution were recruited in Cameroon. Grants came from the USAID, the Mellon Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999, scientists conducted a safety trial with a group of prostituted women picked from a truck stop in South Africa. A safety trial is the first phase of a trial involving human subjects. It is the riskiest phase of the trial and should thus not be conducted on populations already at risk — something the researchers themselves concede.

The final study on the matter, which led to the end of research on nonoxynol-9 as a potential solution for HIV, came from Lut Van Damme and colleagues in 2002. Their trial, conducted from 1996 to 2000, was partially sponsored by UNAIDS. It involved 892 women in prostitution recruited in South Africa, Benin, Thailand, and Côte d’Ivoire. The authors concluded “that nonoxynol-9 increased risk of HIV-1 prevention compared with placebo.” The overuse of the gel provoked vaginal lesions in women in prostitution which in turn left them infected with HIV — a result only confirming previous findings. Researchers acknowledge that the number of seroconversions might have been even underestimated, given that there were more women who left the trial in the nonoxynol-9 group than in the placebo one.

Ethics of clinical trials on women in prostitution

Documents such as the Nuremberg Code from 1947, the Declaration of Helsinki adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964 or the Belmont Report from 1979 outline basic principles to follow when conducting medical research on human subjects. Despite having been approved by several ethical committees, the nonoxynol-9 clinical trials were at odds with such principles, as researchers and sponsors alike admit.

Vulnerable women and girls in prostitution targeted against ethical standards

A 1998 UNAIDS technical update on microbicide studies (mainly nonoxynol-9) states:

"Ethical issues, such as the validity of informed consent when underprivileged and undereducated women at high risk of HIV infection are asked to participate in microbicide efficacy studies have to be resolved."

Yet the same document recommends, for “efficiency,” conducting research in “developing countries where HIV incidence is high” and on “post-natal women” and “teenage girls or university students” who are at high risk of HIV infection.

Professor Jean-Philippe Chippaux, an expert on clinical research on human subjects in Africa, and most notably on ethical failures during HIV trials, spoke to 4W at length about the complexities of this type of research which he said requires “extreme caution.” However, he adds:

“Research on vulnerable populations should not be ruled out. Women for a long time were excluded because of their perceived vulnerability but that had the perverse effect of medication not suited to their needs and a loss of chance to promptly benefit from a new treatment.”

His fair point echoes the principle laid out by the Code of Helsinki that calls for a just balance between the beneficiaries and the risk-takers for any medical research.

However, the studies were carried out on women in prostitution precisely because of their compromised position with respect to men who pose as “clients.” The imbalance of sexual power between men and women — felt most vividly in prostitution — means that it is men who transmit STDs to women through sexual violence and by refusing to wear condoms.

The vulnerability of the women recruited for the nonoxynol-9 trials did not stop with prostitution, though. In the Lut Van Damme study published in 2002, participants in South Africa only had to be 16 or older to be enrolled in the study. There is no mention of extra safeguarding measures for the minor participants in the study.

Ironically, South Africa ratified the UN Convention for the Rights of the Child in 1995, one year before the trial, which urges state parties to take measures to prevent child prostitution. One arm of the UN claimed to aim to abolish child prostitution while another used child sex trade victims for research.

In the same study, 80 percent of the women in prostitution recruited in Cotonou were foreign to Benin. Most participants who did not return for the study had moved to another city or even country. This rings the Palermo Protocol bell. The UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons defines trafficking, among other things, as the transportation for the purposes of prostitution. There is no evidence to suggest study participants, including minors, were rendered aid by the UN as potential victims of sex trafficking during or following the completion of the UN-funded study.

Researchers admit they lacked informed consent in HIV studies on prostituted women and girls

Informed consent is an ethical pillar of trials on human subjects. According to the FDA, informed consent requires “facilitating the potential subject's comprehension of the information” and that “the process must provide sufficient opportunity for the subject to consider whether to participate.”

There are exceptions to when informed consent much be given, but these are only considered in extreme cases such as when a person is incapacitated or in life-threatening situations. Children under the age of 17 are generally not considered capable of providing informed consent.

In the 2002 study in South Africa, Benin, Thailand, and Côte d’Ivoire, evidence from within the study itself indicates that the researchers were not able to obtain informed consent. Three months into the research, 70 percent of the women in Durban in South Africa “did not understand the study fully.” Ninety-eight percent of nearly 900 participants did not understand that the placebo and the nonoxynol-9 gel did not offer the same type of protection against HIV. It was only five months into the trial that an acceptable majority (82.5%) understood the meaning of placebo. The authors admit that “obtaining truly informed consent was difficult to achieve.”

This detailed information comes from a paper published in 2000 by the same authors, Van Damme and colleagues, that discusses the ethical limitations of their study. There is no similar extended analysis available for other papers. While the authors are honest about their failures, their inaction and that of the numerous ethical boards that approved the trial is concerning.

Ethical failures in HIV trials on prostituted women ignored in mainstream media

Apart from the odd article here or there, there was no major outcry surrounding the ethics of the trials. Investigators like Michel Alary, among others, continued research on HIV through women in prostitution. Some later went on to have successful careers. Léopold Zekeng is UNAIDS Country Director for Tanzania. Lut Van Damme now works for the Gates Foundation. Her study colleague Gita Ramjee even conferred her a FHI360 (formerly FHI) lifetime achievement award. Both had experimented for years on women in prostitution.

Nonoxynol-9 was just the beginning. These papers were part of the early wave of academic use of the term “sex worker” well before it was normalized (even The New York Times reported the trials with the term “prostitute”). This strategic use of language benefited the researchers by obscuring the fact that they were experimenting on victims of prostitution. Women and girls were written to seem like active participants in their “work,” while their rapists were described as “sexual partners.” Had they written they were going to experiment on “female victims of male violence,” perhaps the prestigious academic journals in which they published — The Lancet, The New England Journal of Medicine — might have been more reticent.

The uncritical view on prostitution held by medical researchers marked the start of a decade of collaboration with self-proclaimed “sex worker” organizations which are favorable to pimping.

The PreP trials

As much as the nonoxynol-9 trials virtually escaped public scrutiny, just a few years later, in 2004, the Tenofovir® trials sparked a media frenzy. That year, the Gates Foundation sponsored a series of trials on Tenofovir provided by the US pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences. Tenofovir (commercial name: Viread) was used in the treatment of HIV or “antiretroviral therapy,” but its efficacy as a preventive treatment for HIV — “pre-exposure prophylaxis” or “PreP” — was unknown. Women in prostitution, once again, appeared to be the ideal population to find out. This time, things did not run as smoothly as expected.

A study in Cambodia meant to recruit 960 women in prostitution was halted after objections from the pro-prostitution NGO Women for Unity, member of the notorious pro-pimping lobby, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) whose former vice-president Alejandra Gil was convicted of sex trafficking. The NGO united with the Asia-Pacific Network of Sex Workers, another member of the NSWP and Act-Up Paris, also in favor of the decriminalization of pimping, to stage a protest at the 2004 AIDS Conference in Bangkok, Thailand, where the Gilead Booth was sabotaged.

A few months later, French media revealed similar trials were being held in Cameroon where 400 women, most of whom were in prostitution, were recruited. Just as in Cambodia, public scrutiny led to the government closure of the trials in February 2005.

What was missed all along was the nonoxynol-9 case. Yet, certain names re-emerged. Ronald E. Roddy was also an investigator in the Cameroon trial that was halted. At the time, he worked for the Gates Foundation, as was declared in the paper published in 2007 under “competing interests.”

The aftermath has been just as interesting and overlooked. It marked a whole new modus operandi for clinical trials on women in prostitution: the funding by international organizations and U.S. donors of pro-prostitution organizations to ensure access to women.

Research collaboration with pro-prostitution NGOs

The principal investigator of the aborted Cambodia trial, Kimberley Shafer Page, reportedly stated that the closure represented a new opportunity — the collaboration with “sex worker” organizations, which might or might not include pimps, to access women in prostitution to conduct even more trials.

Thanks to the Cambodia Women’s Development Association that helped her recruit subject participants, she co-investigated the prevalence of HIV in prostituted women and girls aged 15 to 29. The Cambodia Women’s Development Association is a local NGO that funded the Cambodia Prostitution Union and is a member of the GAATW, the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women, another pro-prostitution lobby. Neither the NGO nor researchers show any particular concern for the overall well-being of prostituted women and girls beyond HIV.

Similarly, the NGO that rejected the Tefonovir trials, Women’s Network for Unity, now purports to be funded by the likes of FHI360 (former FHI), UNAIDS and WHO.

Bea Vuylsteke, a former investigator on nonoxynol-9, joined the WHO Technical Reference Group in 2005 to prepare the “Toolkit for Targeted HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care in Sex Work Settings.” Prominent members of the NSWP and the Dutch pro-prostitution group TAMPEP (Transnational AIDS/STI Prevention Among Migrant Prostitutes in Europe) were among the collaborators.

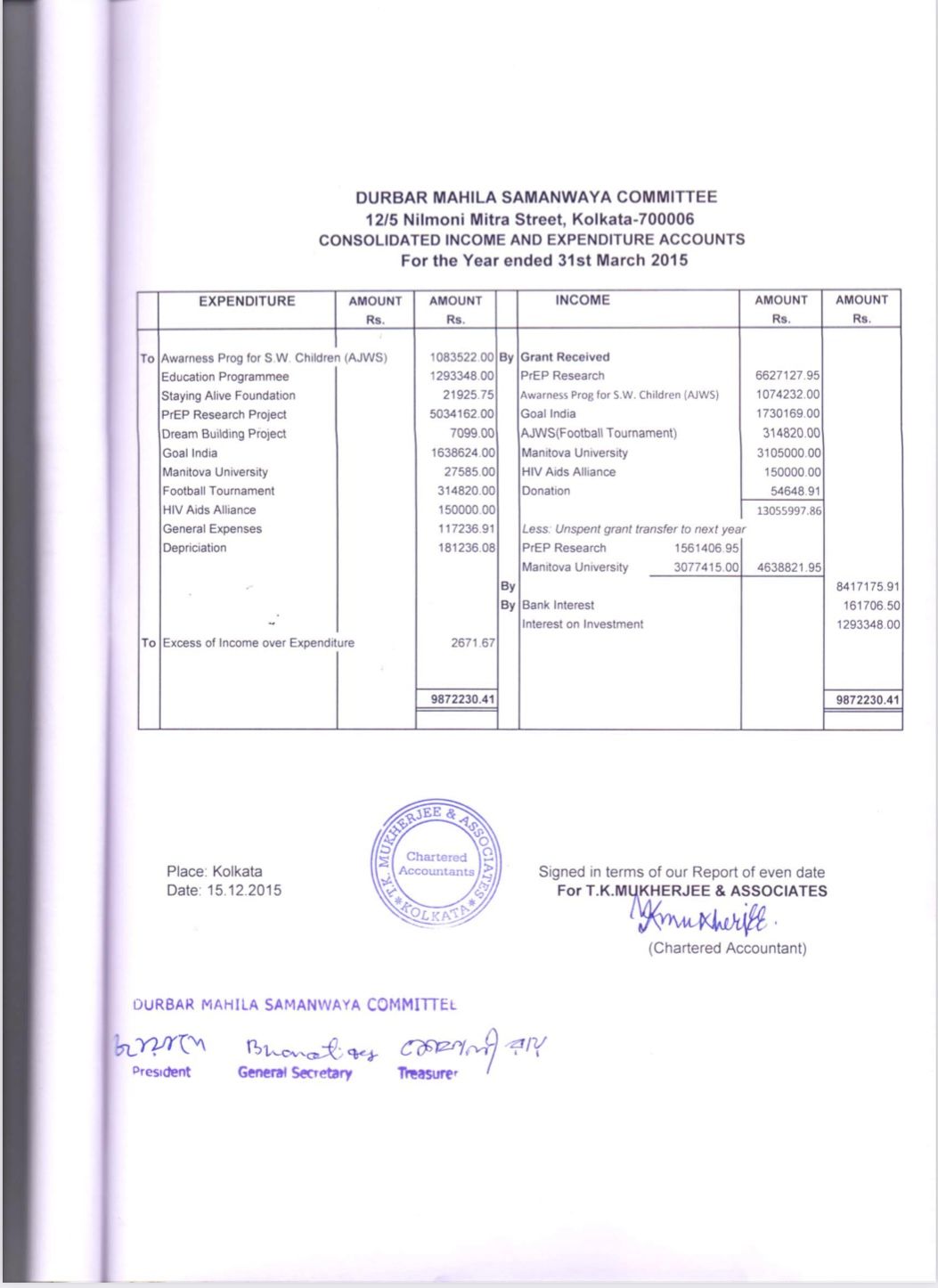

The case of the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC) is particularly enlightening. The DMSC is a staunch lobbyist for the decriminalization of pimping in India. The organization was founded in 1995 to monitor and prevent HIV transmission in Sonagachi, which feminist academic Janice Raymond calls the “biggest brothel area (she) has seen within the smallest plot of land” with an estimated 10, 000 prostituted women. Men also violate girls in Sonagachi, girls that are either violently trafficked into the brothel or born in it. The DMSC provides no exit solution to women and girls in prostitution in Sonagachi, focusing instead on the reframing of rapists as mere “buyers” of “sex work.”

None of this information stopped the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a “nonprofit fighting poverty, disease and inequity around the world” from donating USD 1 million to the DMSC in 2003, and later funding a demonstration project conducted by the organization in 2014. Contrary to an interventional trial like those of the nonoxynol-9, the purpose of a demonstration project is not testing the efficacy of a given drug but assessing the use of a treatment in a real-life setting: it’s about transferring the clinical to human scale.

The PreP-India research project was carried out in collaboration with the University of Manitoba in Canada, the WHO, the DMSC and Ashodaya Samithi, another Indian pro-prostitution entity based in Mysore. In the Calcutta branch of the research, approved among others by the Institutional Review Boards of the DMSC, PreP was distributed through a contract with Gilead Sciences which “provided additional support for data management and post trial follow-up.”

About 600 women were recruited to take a daily PreP pill. The few women that dropped out did so mainly because they were no longer prostituted or because of side effects. Almost half of the women (42%) were illiterate.

These types of demonstration projects on women in prostitution are still ongoing around the world.

The majority of the people and entities cited declined to comment or could not be reached.

The generous support of our readers allows 4W to pay our all-female staff and over 50 writers across the globe for original articles and reporting you can’t find anywhere else. Like our work? Become a monthly donor!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments