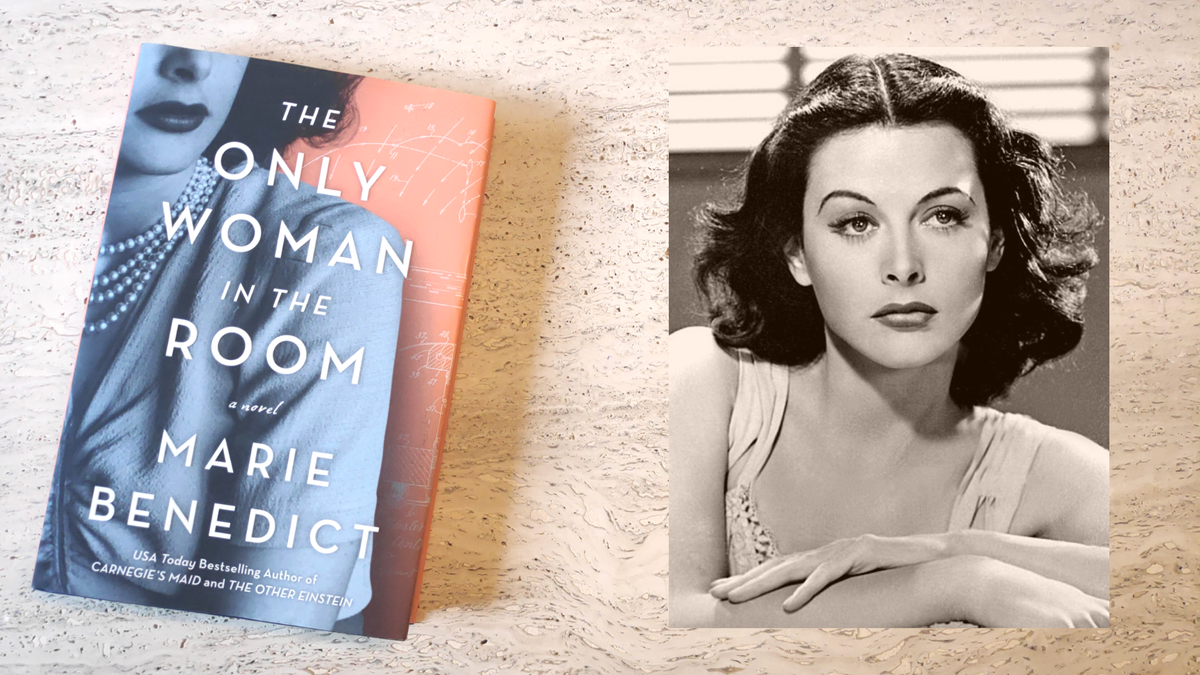

‘The Only Woman in the Room’ Demonstrates the Maddening Tragedy of Brilliant Women

Hedy Lamarr’s story is heartbreaking and infuriating.

Warning: This post contains spoilers for Marie Benedict’s “The Only Woman in the Room,” although all spoilers are also just historical facts. Proceed at your own discretion.

When I finished Marie Benedict’s latest historical fiction novel, “The Only Woman in the Room,” I was furious; I wanted to throw the book across the room. I immediately texted my best friend with a photo of the cover, “Have you read this?? UGH I hate men!!”

It wasn’t a bad book. There are valid criticisms of it, sure. But that’s not why I was fuming.

I was mad because Hedy Lamarr, the subject of the book, was never truly vindicated. She was beaten and broken down by the patriarchy, and it seems the patriarchy won. I was mad for her, and for every other woman like her throughout history whose stories we would never know.

Benedict’s fictionalized account of Lamarr’s life shows us sides of the actress of which few are aware. Her mysterious past as the wife of a Nazi arms dealer, victim of domestic violence, war refugee, and scientist paints a picture of a brilliant mind that was stifled by the strict gender roles of the time. To this day, she is still known by most as only a pretty face.

The story opens with Hedy as a young actress in Vienna in 1933 (known by her birth name, Keisler, at the time). Hedy was doggedly pursued by Friedrich “Fritz ”Mandl, an Austrian arms dealer. When Hedy married Fritz in an effort to protect her Jewish family during the coming war, she had little idea what she was truly getting into.

"It wasn’t until the 1990s, over fifty years after she submitted her invention for patenting, that she finally received credit."

Hedy found herself in an abusive marriage with one of the most powerful arms dealers in the region. He kept her locked away, only allowed to leave with his permission. Her sole purpose in the house was to come out during his important meetings with Austrian and Italian officials and serve as eye candy, her silent beauty underscoring Fritz’s power.

During these meetings, Hedy learned secrets about the weapons systems that would eventually be used by the Third Reich against her own people. When Fritz, previously on the side of Austrian independence, surrendered to the Nazis and agreed to sell his munitions to Hitler, Hedy fled — taking their secrets with her to Hollywood. There, she dropped her German and Jewish heritage and became known as Hedy Lamarr: movie star.

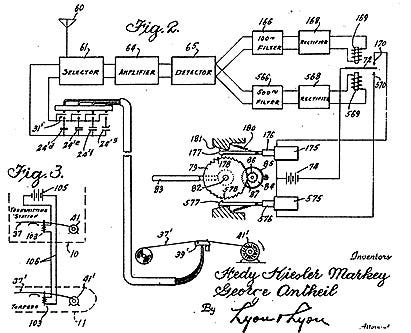

In 1940, using the knowledge she had gained in Austria, Lamarr and composer George Antheil invented a frequency-hopping system designed to allow remote torpedos to avoid enemy frequency jamming. This invention solved a major problem facing the U.S. Navy and was patented with a Top Secret classification in 1942. The Navy, however, refused to use it.

The invention was essentially ignored until after the war, when the Navy used it in developing a “sonobuoy” system. From there, according to NPR, “the whole system just spread like wildfire.” In 1985 it was declassified.

Spread-spectrum technology, as it came to be called, laid the groundwork for most of today’s wireless communication systems.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, over fifty years after she submitted her invention for patenting, that she finally received credit. Supposedly, when she was called by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and informed that she was receiving the Pioneer Award for her work, she responded, “Well, it’s about time.”

She was absolutely right.

By the time Lamarr received the award she was 82 years old, and was leading a life of seclusion in her Miami home. She died three years later, essentially alone.

The penultimate chapter of “The Only Woman in the Room” imagines Hedy’s reaction to her invention’s rejection by the Navy:

“All the rage storming within me evaporated, leaving a hollow, if beautiful, shell. Perhaps the shell was all this world wanted from me.”

By the end of her life, Lamarr did seem but a shell of her former self. Patriarchy, apparently, had finally beat her into submission. Her brilliant mind was no protection. In fact, Lamarr’s story made me wonder if brilliant women are doomed to a particular type of patriarchal tragedy.

Like Charlie, the narrator in Daniel Keys’ short story Flowers for Algernon, brilliant women are not only doomed to have their contributions rejected and ignored in a man’s world, but also to watch the withering and wasting away of their own intelligence. Women like Lamarr have front-row tickets to their own tragedy, fully aware of the impacts of the loss of their potential both on themselves and society.

“I am afraid. Not of life, or death, or nothingness, but of wasting it as if I had never been.” - Flowers for Algernon

Lamarr seemed to move from one prison to the next. She escaped the prison of her abusive husband Fritz only to live the rest of her life in the prison of her own body. It would be, as one can imagine, truly maddening.

Today, thanks to the feminists who have pushed for change, women in The United States have more freedom and opportunity than those of Lamarr’s time. We are allowed to become scientists, inventors, and technologists. We are allowed to use our minds and to serve as more than a pretty face. The barriers are lower, although they still remain in more subtle forms.

Yet, in many cases, a brilliant woman is still nothing more than a “wife.” Consider, for example, the recent case of Esther Duflo, who won the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics along with her husband and another male colleague.

The headline in The Economic Times read: “Indian-American MIT Prof Abhijit Banerjee and wife wins Nobel in Economics.”

Duflo is the second woman ever to win the Nobel prize in economics, and the youngest ever to do so. She has a PhD in economics from MIT, where she is now one of the youngest professors to have been awarded tenure.

Duflo, at least, is allowed to do her work and is receiving contemporary recognition for it. In many parts of the world, girls are still denied even the most basic education, based solely on their sex.

Reading “The Only Woman in the Room” begs some painful questions:

- How many other women throughout history have had their contributions erased and ignored?

- How many have fought to be allowed in the room only to be eventually defeated and broken?

- How many brilliant minds were lost not to illness or death, but to patriarchy?

- How many inventors, engineers, or economists are still trapped in a female body, never to be allowed out?

The maddening isolation of being a woman with a brilliant mind has historically been, and in many cases still is, a tragedy. For many women, there will be no vindication. Lamarr’s small victories in recognition over half a century later are not enough to make up for a lifetime of hollowing herself out to cope with the pain.

This book, the PBS documentary, even this very article — none of it is enough. This is why “The Only Woman in the Room” made me furious. She deserved more. Women deserve more.

The generous support of our readers allows 4W to pay our all-female staff and over 50 writers across the globe for original articles and reporting you can’t find anywhere else. Like our work? Become a monthly donor!

Enter your email below to sign in or become a 4W member and join the conversation.

(Already did this? Try refreshing the page!)

Comments